Scrum.as - Blog

2016-02-07 - Scrum Master as a Coach

This article is a part of the new certification International Scrum Master Advanced - become a Scrum Master Guru... It will be ready end February 2016

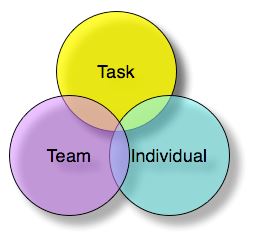

Coaching a team means working on two levels: the group level and one-on-one. That means shaping the talents of individual team members and then fitting them together in a powerful single unit - the team. It also means not sitting back and hoping that one wave of the magic wand brings everyone together in a team.

Transition can be tough on individuals - members of your new team - who have grown comfortable operating more or less independently. In the new team environment, where success depends heavily on inter dependence and mutual accountability, some free spirits may suddenly feel boxed in. Managers need to be patient.

Here, we concentrate entirely on you, the manager, and the best way for you to lead with teams - as a coach. Managing a team requires the application of a certain set of skills that you may not have needed much when you were in charge of a department of amiable and cooperative but independent workers. If you want to become an effective team leader, you have to make adjustments, too.

When managers move into team situations, they sometimes fall into what we call the all-or-nothing trap:

All - you direct all activities of the team. You explain (to yourself) that they (your team's members) cHelenaot do anything yet for themselves. Although you are trying to be helpful, you actually come across as a dictator. In the process, you stifle team members' initiative, creativity, and quite possibly their entire motivation.

Nothing - you stand back and let the team do everything for itself. You tell yourself, "I don't want to get in their way." In this hands-off style, you come across not only as uninvolved but also as uninterested, and you unknowingly plant the seeds for a bumper crop of chaos and frustration - not exactly the way to grow a team!

The key in managing teams so that they achieve high performance is finding that happy medium between the all approach and the nothing approach. We show you the way - how to be a coach but not a dictator. Here, we talk about the way successful team managers behave in any situation, whether they supervise the team members or serve as a leader among peers. The here even apply to coaches who now have no supervisory authority at all, like when they are on temporary assignment in a cross-functional situation.

Working as a Coach

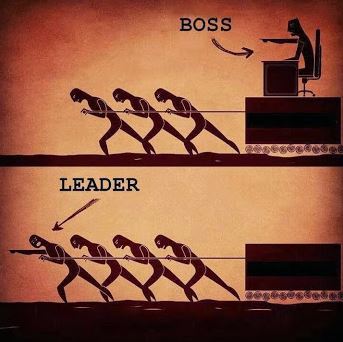

This first section defines what leading teams, as a coach is all about. It distinguishes the role of coach from the way many managers commonly function, as a hands-off and distant observer or as a very hands-on, dominating boss.

Doer vs Coach

Managers in all types of organizations often function as doers rather than coaches. They put greater emphasis on doing work themselves and much less emphasis on developing and motivating staff members to do the job on their own initiative. With teams, managing as a doer can be problematic. The following story is a common one in many workplaces.

Marco was assigned to manage a cross-functional project team with a critical mission at IT software Development Company in south of Basil. Initially, he met with the seven members of the scrum team to scope the project and make individual assignments. Everyone nodded with understanding when Marco explained that the team's mission was crucial to landing a sizable, long-term contract. They took reams of notes as Marco spoke, and he felt pretty good as the meeting ends. "They're ready to go," he thought. The project had a deadline of four months.

As the weeks rolled past, Marco was busy with his part of the project. He occasionally checked to see how individual team members were doing. However, the entire team did not get together on any regular basis.

At the beginning of Month 4, Marco became aware, almost by accident, of a big disconnect between the project's developers and tester functions. He heard a couple of team members griping about the problem. "We better meet quickly," Marco thought. He pulled the team together in an emergency session. Working many extra hours during the next few weeks (Marco especially) with only two deadline slippages, Marco's team got the project done - in just under six months. Upper management was unhappy with the delay but kept the new customer on the line and finally reeled in the big new account.

Marco breathed a sigh of relief when the project ended, but he was not happy about the whole experience. Leading this project team was a difficult job. He encountered problems with team members sometimes getting off track from what they needed to focus on, occasionally duplicating efforts, leaving tasks undone, and clashing over what the project objectives were.

Characteristic of his own operating style, Marco often stepped in, picking up work that team members dropped and solving problems team members encountered. Sure, the team pulled together to get the project done, but Marco thought the overall quality of work was not as good as it should have been.

Why doers (like Marco) feel frustrated

I am sure you can guess the main reasons Marco's team did not produce as well as he expected:

Lack of planning: The team did not operate with any kind of documented sprint planning. Each team member had his or her own understanding of what should happen. Objectives and assignments were not fully clarified. The results were conflict, duplication of effort, and work left undone.

Lack of regular progress review: Marco met sporadically with individual team members. He did not pull the team together in daily meetings unless a big problem surfaced. He did not have any status review sessions so that team members could discuss overall progress and unsolved issues, no matter how trivial.

Marco acted as a doer, not a coach: Marco was team leader more by title than by action. He did little actual scrum coaching of team members as a whole or as individuals. He was the classic doer, rescuing the team by picking up any (and all) slack and confronting and solving most of the problems himself.

What coaches of teams do that doers usually don't do

Leaders who are doers (like Marco, earlier) often are stuck in day-to-day operations and tied up in their own work. For such leaders, time is a constant squeeze; every day becomes a series of interruptions. Leaders working as doers may be the top individual producers for the team, the ones who pull it through - just the way they did on projects back in school. Trouble is, they rarely have the organization and discipline necessary for leading a team and coaching its members.

Managers working as coaches are doers, too. They have tasks of one kind or another as they help the team achieve its goals, but, unlike doers, managers as coaches do work that is appropriate to their role. They function at a higher level, by leveraging their people resources - multiplying the effect of their team members by doing the following:

Meeting regularly. Coaches pull their teams together, meeting some kind of regular basis. At their meetings, they set plans, review the status of work, and address and solve problems. In doing so, they ensure that the team stays focused and on track. Coaches also meet with individual team members, keeping in touch and working with them so they perform well within the team structure. In contrast, managers as doers infrequently meet (if at all) with the entire team and thereby tend to leave issues to chance.

Managing by plan. Managers as coaches want to clarify commitment and responsibilities and define objectives and assignments with their team members so they can develop schedules and set action items when they meet together. In simple terms, everything the team does is part of a plan (the sprint), and the coach manages the team by that plan. Although it may be adjusted over time, the plan serves as a guide for the team to commit to. Coaches also ensure that all-important matters are documented (light weight documentation). Nothing critical is left to memory. Doers, meanwhile, tend to be more reactive, dealing with tasks and issues as they arise. They do much less in the way of planning for themselves, let alone their teams.

Giving lots of feedback. Coaches regularly provide performance feedback about overall group effort to their teams and about individual matters one-on-one to their team members. Coaches cite examples of specific team behaviour when letting people know what they are doing well and what they need to do better (making the retrospective meetings work). The team and each of its members know how well they are performing when they work for a manager who functions as a coach. Doers give much less direct performance feedback. If big problems arise, they may say something. Nevertheless, they are often too busy with their own activities to stop and directly acknowledge the performance of their team and its members.

Helping resolve problems and conflicts. When problems arise affecting how work is done, coaches work with their teams to address and resolve the issues. Problems are a normal part of any work operation. Coaches work to solve problems, not to evade dealing with them or to assign blame. Doers, like in the story of our friend Joe, are diligent workers who look like they have all the answers. However, coaches know that they do not have to shoulder that enormous burden all by themselves because they can involve others - team members closest to problems - to help work out solutions. When personal conflicts arise on a team, coaches get team members to work out their differences. Coaches know that conflicts left unaddressed fester and can disrupt a team. By comparison, doer types often avoid personal matters, hoping they will work themselves out - management by osmosis!

Pushing accountability. Managers as coaches push team members to take responsibility and produce at high levels. The main techniques coaches use are regularly reviewing progress, addressing issues as they arise, and giving constant feedback - all in the name of high standards of performance. Hands-off doer managers certainly want their team members to achieve top results but seldom take any action to ensure that outcome, leaving much to chance. That laid-back approach ends in frustration when team members fail to perform as needed.

Putting an emphasis on mentoring. A big part of coaching involves mentoring - challenging your people to do better and supporting their development. Such efforts can range from discussions about their career interests and mapping career paths to posing tough questions that help staff figure out solutions on their own. Mentoring emphasizes working with team members so that they can handle responsibility in a self-sufficient way.

Managers who lead their teams as coaches try to use the time they spend with their people wisely. Because they do not have much time to give, they emphasize quality time. A manager as a coach knows she does not have time to waste, so she makes every bit of it count. Doers do not seem to grasp that idea. They may not shirk hard work, but they just waste a lot of time and energy running from one activity to another.

Boss vs Coach

Some managers with a broad doer streak in their makeup do, nevertheless, assert leadership. They are willing to step in and take charge of their work groups and often play the role of boss in doing so. As the boss, they call all the shots.

a boss-manager

Helena was a take-charge type manager in the marketing department of a consultant company in the Texas area of us. She determined what each person in her group needed to work on and how that work should be done. When anyone complained, Helena pushed hard and those workers usually fell in line. At the same time, because all workers were interdependent, Helena wanted to see her group develop into a team, and she thought the opportunity was coming soon.

Helena's boss hinted that the rollout of a new over-the-counter product might be assigned to her. To get the work done and out the door, all five staff had to work closer together when they seldom had before. Helena coveted the assignment, but she said nothing to her staff members, reasoning that doing so might distract them from their current assignments. She would clue them in when the project was assigned.

Then one day, 15 minutes before Helena was due at her boss's weekly staff meeting, he called telling her the important project was a go and that she needed to get it rolling ASAP. Helena sprang into action, running to each staff member's office delivering the good news and making assignments. "Drop what you're doing and make this your top priority," she declared, offering no assurances to their bewilderment. "Look - don't worry about what you're doing now," Helena said. "You know how to do what I've told you here. And make sure you work well as a team on this one!"

Helena felt relieved as she rushed off to her boss's staff meeting. Her project was launched, and she would meet with her team next week for progress review and Q&A. What Helena did not know was that her staff met informally as a team even before the scheduled team meeting to complain about their confusion and Helena's dictatorial style.

Why Helena's team struggled

A manager as boss takes charge and runs the group as she sees fit. However, she often leaves her staff in a dependent role, waiting to be told what to do and what is going to happen. This hit-and-run, tell-them-what-to-do style lets the team know whose boss, but it also leaves them in confusion. Without planning and two-way communication, people are not prepared to work as a team. In fact, Helena, the hero of the story, is causing a team to form. Nevertheless, her people are coming together for the worst possible reason: They have a common enemy - the boss!

Many managers like Helena try to be good bosses. They assert themselves and have good control over their groups. However, their take-charge, do-as-I-say approach, although quick, usually does not lead to the development of a group as a finely tuned, functioning team.

Teams need leadership to develop and perform, but managers who are absorbed in the work and control it with a heavy hand are not providing the leadership that teams need. Their efforts lessen teamwork and heighten dependency - the opposites of what you want to achieve in managing a team.

Leading by Example

As a manager, you are in the spotlight - all the time. You are the most-watched person in the group and your behaviour influences everyone else. I offer no guarantees, but when you set the right example, you greatly increase the likelihood that you will get the performance that you want from your team members. Set the wrong example and - do we need to explain the down side.

Avoiding the credibility busters

You do not need to be perfect to function as an effective team manager. However, you do need to avoid certain kinds of behaviour that can damage your credibility - and disillusion your followers. Making apologies for your bad behaviour will not make it go away, so here is my check-off list of credibility busters:

Starting, stopping, changing. Team members need to see you stay the course and stick with the plan from beginning to end. Sure, good reasons exist for making mid-plan corrections. But if you change directions again and again because you haven't thought things through in advance - with the team, you leave the team confused and doubtful that any progress is going to be made under your leadership.

Shooting the messenger. Managers often say to team members, "Tell me if you're having any problems - I want to know right away." In addition, when a team member reports bad news, some managers explode in anger. That is called shooting the messenger. If your people do not feel safe bringing issues to you when they first arise, you may hear about them much later, when the molehills have turned into mountains.

Staying out of sight. When managers of teams seldom are visible to team members, their leadership tends to have little positive effect. "Out of sight" definitely becomes "Out of mind" for most team members. They do not see you, so they do not know you; and as a result, you do not command much respect. You can give all the reasons you want for why you are wrapped up in other important matters, but excuses neither make up for your lack of visibility nor provide motivational leadership for the team.

Talking often, listening seldom. One of the big credibility busters that I hear employees remark about is having a manager who talks too much but does not listen. When team members come to you discussing issues or sharing other news yet having to fight hard to get a word in, you prove that you are not a resource for them. Managers as coaches invite two-way conversations, and they can listen to understand.

Dominating more than facilitating. Breaking this old habit is one of the biggest challenges many bosses face as they seek to become coaches and team leaders. The team needs you less to take charge and more to guide its discussions in planning and problem solving - and in getting everyone involved. That is the essence of good facilitation, which I talk more about in Chapter 12.

Avoiding, avoiding, avoiding. Problems are inevitable in every work situation. Some problems need direct involvement by the manager, especially when they involve sensitive issues like operations or personnel that require negotiation with management upward and outward from the team. When the manager is one who never met problem he could not avoid, you have a team swamped in chaos and frustration.

Making commitments, failing to meet them. Lack of follow-through is another deadly disease that kills manager credibility. This behaviour is akin to a politician making promises on the campaign trail and forgetting them once elected. Politicians who do not follow through often get voted out at the next election. Team managers who make false promises lose their following even faster.

Looking Ahead While You Keep the Team Focused on the Here and Now

Leading teams as a coach goes beyond leading by example. It also requires communicating about the long term at the same time that you review progress on the current agenda - in other words, staying involved with the team on the day-to-day work while providing a sense of direction toward the future. This section explores the key behaviours you want to demonstrate in that dual role.

Looking forward to be forward looking

An important ingredient team's need from their leaders is a sense of direction. A sense of direction answers questions like: Where are we going? Why are we going there? Moreover, what are we going to accomplish in the end? To avoid becoming aimless, your team needs answers. This is what you can do to help give the team a clear sense of direction:

Communicate a vision. A vision is a picture of the future. It shows your team how it will function when it is thriving sometime in the future, and it serves as the guiding light for getting there. Good leaders provide a vision. Even if you lead a team with a short time frame for its work, you want to communicate the overall good results that you expect to see in the end. A vision galvanizes people to move in a direction together, and that is what you want if you are seeking a high-performing team.

Talk up your vision and share other vital future information. Communicating your vision is only the beginning of helping your team see the big picture. Make your vision a recurring theme. Bring it up in conversations with team members. Relate it to what is happening to team members in their work, to decisions the team is making, and to the evaluation of team progress. When you talk about the vision, formally and informally, to the whole group or individual members, it comes alive and, over time, grows stronger as the guiding light. In addition, do not forget to share news about the organization's plans and progress. Let the team know where the business is going and how the team fits into the big picture. (You may need to take the initiative on this one, finding out from management above you. Again, no passive coaches need apply for team leadership roles!)

Set goals. Working with the team, determine the important results the team needs to accomplish so its vision comes to fruition. Coaches focus people on producing results; doers tend to be task oriented - let us just get the work done. Without goals for results, people are busy but not necessarily productive.

Develop action plans. Coaches manage by planning. Managers who function as coaches work with their teams to set plans that define how goals are to be achieved. The plans serve as the road maps, showing team members the key steps to be taken and the roles and assignments along the way. Plans may change as needs change, and that is okay. Plans minimize seat-of-the-pants operations and reduce team frustration.

Challenging and encouraging excellence

Managing as a coach means challenging and encouraging your team members to achieve high quality performance in their day-to-day work. Here are key things that you can do to encourage excellence:

Review progress regularly. Coaches let their teams know how they are doing, individually and as a team. That way, everyone knows where he or she and he or she stand.

Provide constructive feedback. Constructive feedback means telling someone what you notice about that person's job performance. It acknowledges what was done well - called positive feedback - and what was done less well, where improvement is needed - called negative feedback. Although it can be written, professional-quality feedback is offered informally, often one-on-one in a conversation, and it meets these guidelines:

- The instance of performance that is being discussed is stated up front.

- For clarity, performance is described in specific terms, not generalities.

- Feedback is delivered directly and sincerely.

- Feedback states observations, not interpretations. You report what you have seen and not what you think about it.

When you are coaching and giving constructive feedback to acknowledge performance, look at this conversation as a two-step process. First, provide the observations-based feedback following the key guidelines of the tool. Second, if you are pointing out a problem, then have a discussion with the individual about how to correct it.

Support professional development. A major part of encouraging excellence in performance is creating opportunities for team members to improve their job skills. Whether done through training classes, cross-training, new assignments, or all those ways, the method matters less than your support of continuous training as normal practice. In fact, sometimes you may even be the teacher, passing on your knowledge and experience in work areas and thus helping team members to improve their skills.

Address problems constructively and in a timely manner. Achieving excellence means dealing with problems that can hinder top performance. It does not mean humiliating people who make mistakes or are performing at less than desired levels, nor does it mean sticking your head in the sand just to avoid hurting anyone's feelings. Managers who function as coaches handle performance issues by coaching to improve. They map out goals and plans with the team member, targeting improvement in performance, with a follow-up review of progress. Problems in getting the work done that affect the whole team are discussed with the whole team. Leading as a coach in these situations usually means acting as a facilitator who guides the team through problem solving. It often means teaching the team to facilitate its own problem-resolution efforts without you being there - that is good coaching!

Recognize successes. Taking people for granted is a Demotivator with a capital D. Good coaching, on the other hand, recognizes success and uses it to motivate more good outcomes in the future. How you recognize success, whether informally with positive feedback to individual team members or in a celebration for the entire group, is less important than making certain that you, in fact, do recognize success in some sincere fashion.

Making Things Happen as a Catalyst and Advocate

Coaching the team as a catalyst or an advocate often is the most challenging behaviour for a manager. As catalyst, you must make things happen with the team, not for the team, and, as an advocate, you must manage upward and outward, supporting your team elsewhere in the organization, as needed. Working as catalyst and advocate challenges you to be assertive, positive, action-oriented, and persistent as needed, direct, and sincere. Nevertheless, you must guard against being passive - just sitting back or aggressive - coming on too strong and harsh.

Lights, camera, action

When you are a catalyst, you organize and cause action. Managers play an important role as catalysts, spurring action on big issues and thereby helping the team to move forward. In the following sections, I discuss a few critical action-oriented behaviours and skills for leading teams in the catalyst mode.

Facilitating the resolution of issues

To facilitate simply means to make easier. Sometimes managers need to intervene, making it easier to make a decision, address a problem, or resolve a conflict or other issues. Facilitating in these situations means bringing parties together, generating full participation in a discussion of the issue, and working toward closure and agreement on what needs to be done next. Your role as manager is to help this process work, but not to dictate it. (Chapter 12 provides you with tools to develop your facilitation skills.)

Your role as catalyst comes into play when the team needs training, especially in the skills that individuals need to work together as team members. Sometimes you can be the hands-on organizer of training; other times you may want to involve team members to assist you. However, you manage the training program, you want to ensure that the training is scheduled and is delivered. The same goes for your team's big performance events or change efforts. These are the kinds of things you want to be closely involved with, assisting team members so that everything happens according to plan - and following up to make sure that it does!

Feel free to join in the training sessions and participate with everyone else. Doing so helps you reinforce the training back on the job and shows you value the training - good leadership by example.

Bringing discussions to closure

People sometimes talk issues to death. The coach's job is to focus people on bringing discussions to closure and defining actions to be taken, which can be done by asking questions like:

- Specifically, what are you going to do to deal with that matter?

- What are your action items here?

- What are your ideas about solving that problem?

- When will you carry out that plan?

Keep the questions you-oriented so that responsibility rests with the team or team member. As you see in the examples, the questions are simple and do not lead a person to answer in any certain way. Give people space to think for themselves. Use what is called open-ended questions, like the first three examples, when you want to generate ideas or thoughts. Close-ended questions are those that can be responded to with a short definitive response, like Yes or No or a specific date, for example. Coaching managers use them when they want to get a commitment of action or agreement, like in the fourth example.

Serving as an advocate

An advocate is someone who defends or pleads a cause for someone else. Advocating is what your team needs from you, their leader, to help them perform successfully. Here are some of the ways you can be an advocate:

Get resources the team needs. To perform well, your team may need materials, tools, time, staff, training, or all the above. Those resources are often beyond the team's reach - someone needs to go get them or budget for them. That is where you come in as manager. Do not wait until your team reaches a point of pain before you go after the resources they need. However, use your head when dealing with the company bureaucracy, especially when you ask for more staff. Wait until the need is truly strong and you can make a solid case to win approval.

Broadcast team successes. This is not about tooting your horn so you look good. It is about making sure your team's successes do not remain secrets. When your group makes gains and delivers good results, let management know. People like to hear good news, so write up your team in a report and talk about them to other groups when you can. If battling for resources is the way it works in your organization, your record of success helps you win favour, especially from management above you. People support winners. Moreover, do not forget the other people. Remember to support other teams when they need something from you or your team.

Make connections for your team. A big part of your role is to know who does what around the organization so you can build working relationships that help get work done efficiently. Sometimes this means serving as the connection for team members who need support from other people. So make that phone call, do that introduction, write that notice of explanation, or join that sensitive meeting - whatever it takes to help your team members going forward and taking responsibility. Promoting self-sufficiency is a major aim of leading teams as a coach.

Help remove obstacles or barriers. Because your team operates within a larger organization, it sometimes runs into organizational obstacles like policies or practices or an obstinate rule enforcer or two in the management bureaucracy. When these obstacles begin to rear their ugly heads, your team needs you as its leader to negotiate upward and outward to minimize, if not remove, these interferences or to navigate around them. Nevertheless, choose your battles and methods carefully, and if you need to challenge someone else in management, do it privately not publicly. Remember, when you make success happen, people tend to listen to you. Your job as occasional barrier buster is a kind of advocacy your team really needs.

Author: Steen Lerche-Jensen

Copyright © 2018 - 2025 by Scrum.as // All Rights Reserved. // Privacy Policy